Your behaviour policy is rubbish. Here’s why.

I’ve read a few thousand behaviour policies, and there is a reason they are invariably so vague. When expectations are vague in a policy, then we know we won’t really fail to deliver what’s written in it. If you’ve attended my training, you’ll know I spend a lot of time talking about specific expectations. However just because we have defined what our perfect scenario might look like, that doesn’t tell us how to achieve this dream.

In my training, I joke that my wife is twenty years into a lifetime project to make me the perfect husband. I say that my lovely wife has approximately a thousand specific targets for me to achieve to make me a better husband, father and human being, and that this list is stuck to the fridge door for easy, daily access. Then I highlight my wife’s obvious intelligence by revealing the secret to her success in this long term project – she only works on two to three targets at one time. She has listed all of her expectations but knows that trying to get me to change in all of these areas is futile. She knows the secret of how to achieve personal change, change in the classroom or organisational change: it needs to be done slowly. This doesn’t mean that fast change is impossible, but in my experience of working with thousands of teachers and hundreds of school leaders, the common factor in unsuccessful change is trying to change too many things at the same time. Actually, you’ll be shocked by how quickly change can be achieved when you focus intently on just two to three very well-defined priorities.

“If you have more than three priorities, you don’t have any.”

Jim Collins, Business Consultant

Pushing a hundred boulders

Imagine one hundred very large, round boulders lined up next to each other in a field, and you’ve been asked to move these enormous, heavy items to the other end of the field. Knowing you could only move one boulder a few centimeters with each energy sapping push, would you move each one a few centimeters and then go back to the first? I’m going to guess you’d go to the first one and focus on getting just one heavy boulder to the other end of the field. Imagine the energy you’d waste running from one boulder to the next just to move each one a few centimetres. Not only is the energy used more efficiently by focusing on one, but when you and others look at the progress that’s been made, one method of change will look like nothing much is different. By focusing on one boulder at a time, the amount of progress is obvious and spurs us on to the next one. We know we can do it. Now imagine that instead of just one person being responsible for moving the boulders, a whole organisation is. This is the role of school leaders. They choose the boulders and they have a much higher chance of success if they focus their energy.

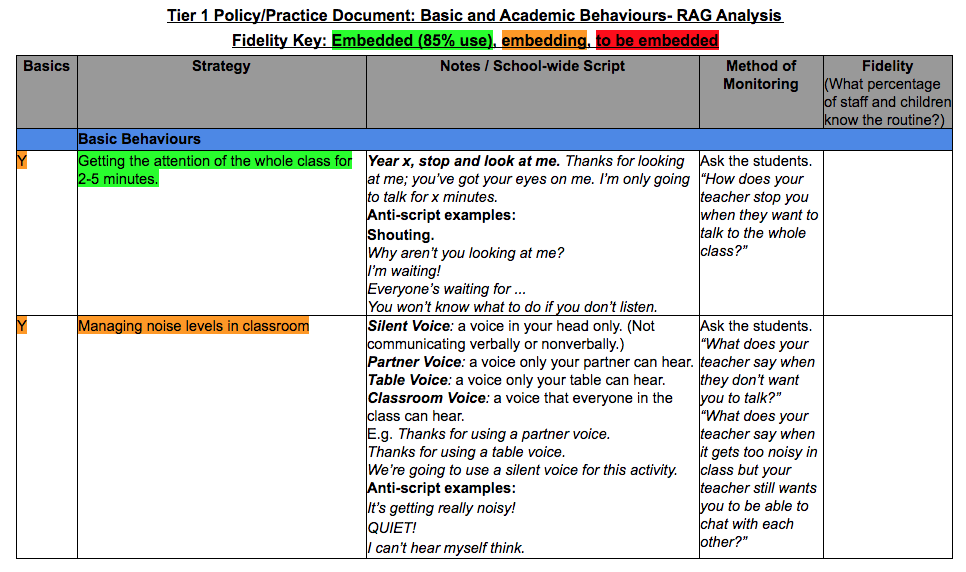

In most behaviour policies there are too many virtual boulders to push. Even the behaviour policies that I’ve read that are more specific in their descriptions of expectations, are invariably a list of things that don’t happen in the school but the school leader wishes they did. Below is an example of a Policy/Practice document and this is key to both defining and realising your expectations.

The Policy/Practice Document

DOWNLOAD YOUR OWN WORD VERSION HERE

The highlighting shows which parts of the policy are actual school-wide practice, which are our current priorities, and which are chosen priorities for some point in the future. Expectations highlighted in green are embedded across school with above 85% fidelity. This means more than 85% of staff use the routine and more than 85% of students know the routine across the school.

We then choose two to three priorities to embed next and highlight them in amber. We don’t choose a hundred things. We choose no-brainers like how to stop groups or children and the language used to teach appropriate noise levels, stuff that every teacher will need. (Later, when you’re embedding harder stuff like metacognitive approaches, then you may decide on specific responses to students who say they are stuck, for example.) These are the routines we’ll have assemblies about, that each class will spend lesson-time embedding, that posters in school will advertise, that will be mentioned in briefings and staff meetings, and whose associated language will be heard ringing out across school for weeks.

How do we know when a routine is embedded? Simple – we ask the children. One of my jobs when I’m working with a school is to talk to two students from each class for two minutes. I ask them, for example, how their teacher stops them when they want the class’s attention.

Here’s an example list of my findings before training with the staff.

- My teacher stops me by:

- Sounding a klaxon

- Counting down from 50

- Shouting “BE QUIET”

- Clapping

- 1-2-3 Eyes on me

- Slowly sobbing and saying, “Please be quiet, I’m retiring in the summer…”

- Shaking a tambourine

- I could go on. There are thousands.

In one primary school I collected over thirty different ways to get children’s attention. This isn’t good. With the Policy/Practice document above you can decide which routines and expectations to embed across school and measure to what extent they are embedded.

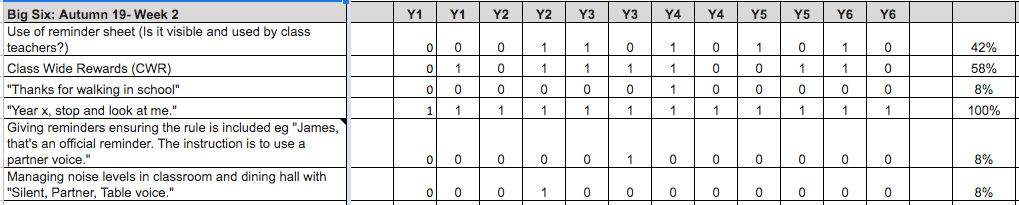

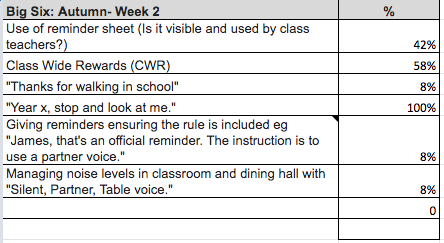

Then we’d feed the results of our research back to staff. We won’t call them out. We’ll just feedback the whole school fidelity percentages. We need to give students and staff much more time to embed routines than we think. Here’s an example of the data. The first one shows what we’d collect. Notice I don’t even name the classes.

This one shows what we’d send out to staff.

My post last week was about how it’s the ‘weigh-in’ element of Weight-Watchers that makes it effective. The Policy/Practice Document is the equivalent of the recipes and the monitoring is the equivalent of the weigh-in. We need both.

The most important bit

Staff need to know that the monitoring is there to make life easier – for everyone. Imagine you’re an NQT and your school gives you a Policy/Practice document like the one above. It simply lists five or six school routines that you know your new class will know. Likewise, those poor, beleaguered colleagues that cover PPA will know that nearly every teacher in school stops their class in the same way (perhaps not every time, but certainly often enough for the class to respond to the instruction instantly).

Consistency. You want it. The students want it. Ofsted want it. This is how to achieve it.

If you’d like a copy of the Policy/Practice document in Word/ Google Doc format or would like a free Behaviour Policy Review, just email me at [email protected].